The Filum Terminale

The Filum Terminale

Last update: 21/10/2019, Dr. Miguel B. Royo Salvador, Medical Board number 10389. Neurosurgeon y Neurologist.

In this section, we want to briefly introduce the normal anatomy of the central nervous system and therewith that of the ligament that can have so many consequences for our patients’ health. The objective is to provide them with a better understanding of the repercussions that their condition can have on the different syndromes and pathologies that we treat.

The Institut Chiari & Siringomielia & Escoliosis de Barcelona (ICSEB) and its neurosurgical team are highly specialized in conditions of the central nervous system related to the Filum Terminale ligament.

As the findings of Dr. M.B. Royo-Salvador’s research of the last 50 years confirmed, a Filum terminale that exerts an excessive traction on the spinal cord causes the Filum Disease. It can consequently be the cause of a clearly defined group of diseases, as well as being closely related to the development of other diagnoses and their prognosis.

Introduction: the central nervous system and the spinal cord

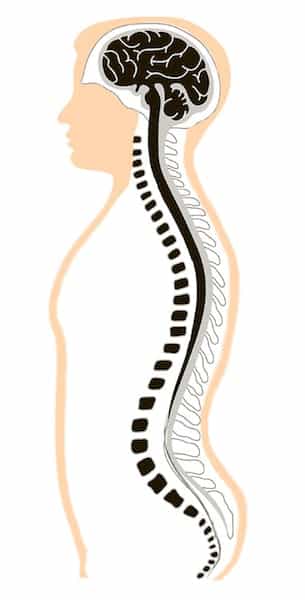

The central nervous system (Fig.1), or neuroaxis, consists of two parts:

- Brain: the portion within the skull.

- Spinal Cord: the inferior or caudal part of the neuroaxis. It has a cylindric shape and is contained within the spinal canal.

The brain is divided into cerebrum, cerebellum and brainstem.

The brain and the spinal cord are wrapped and protected by three membranes, or meninges, which, from inside out, are pia mater, arachnoid and dura mater. They determine two in-between spaces: the intra-arachnoid or subarachnoid space containing cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has the function to cushion, protect, hydrate, nourish and drain the central nervous system; the subdural space is the other one, located underneath the dura mater.

The brainstem connects the brain with the spinal cord. It is made up of the midbrain, the pons and the medulla oblongata.

The spinal cord stretches from the medulla oblongata – which is found in the foramen magnum of the skull – until the first lumbar vertebra. It is flexible, elastic and whitish. It follows the spine adapting to its movements without touching the bones, as it is surrounded by the meninges and CSF.

We can observe the grey matter in a cross-section of the spinal cord, at the central level. It is composed of two lateral columns connected by a grey commissure surrounding the central canal (the medullary continuation of the brain’s ventricular system), giving in the shape of a butterfly, or an “H”, encompassed by white matter.

The spinal canal divides longitudinally into defined medullary segments that are called metameres. A pair of spinal nerves emerge through the intervertebral foramina from each metamere. The spinal cord connects with the peripheral nervous system with 31/33 spinal nerve pairs.

The spinal cord tapers into the conus medullaris at the lumbar level. In the treatises on Human Anatomy and the majority of publications, the conus medullaris is located at the level of intervertebral disc space L1-2. In studies carried out in Spain, with ethnic peculiarities, two authors with relevant publications determine the location of the conus medullaris at T12-L1 level.

The spinal nerve root complex corresponding to the last four lumbar, sacral and coccygeal segments, without spinal cord, make up the cauda equina, resembling a horse’s tail.

The Anatomy of the Filum Terminale

The central nervous system starts to develop during the third week of gestation. This process (neurulation) leads to the formation of the neural tube, which in turn forms the conus medullaris and the terminal ventricle through tunneling and brings about the primitive spinal cord.

The central nervous system starts to develop during the third week of gestation. This process (neurulation) leads to the formation of the neural tube, which in turn forms the conus medullaris and the terminal ventricle, the origin of the primitive spinal cord.

Finally, 38 days into gestation, retrograde differentiation takes place and the filum terminale is formed. From the ninth week of the existence of the human embryo onward, a dysharmonic growth commences between the spine and spinal cord. Two different hormones stimulate the growth and the texture of the Filum terminale slows it down. This produces a mechanical conflict which, in extreme cases, translates into the Filum Disease.

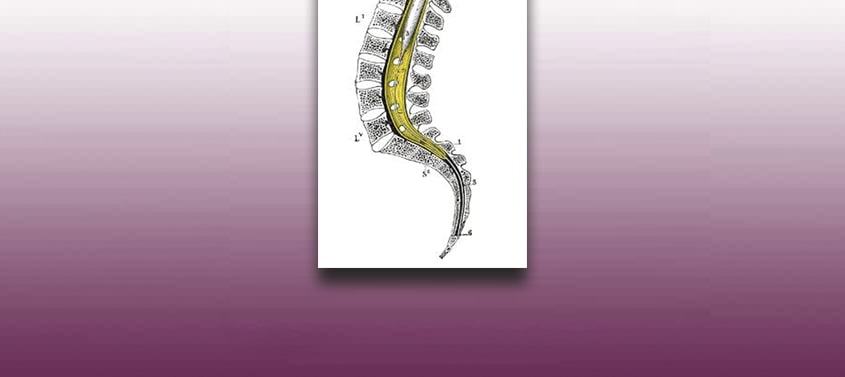

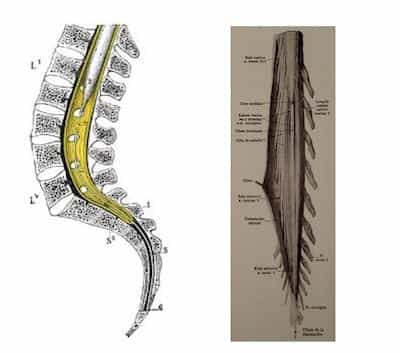

The filum terminale (Fig.2-3) is a 2 mm thick and about 20 cm long filament that extends from the lower end of the conus medullaris until the dorsal side of the coccyx, where it is fixed and remains in place. It is made up of fibrous tissue that continues with that of the pia mater and surrounded by the dura mater until its insertion at S2. There are some nervous filaments that are adhered to its external surface.

The central canal of the spinal cord extends 5-6 cm into the interior of the filum terminale.

Fig. 2 and 3. The Filum Terminale, left, sagittal section of the lumbo-sacro-coccygeal spine; right, conus medullaris with the opening of the dura mater, lumbosacral nervous roots or cauda equina.

The ligament is made up of an upper and a lower part:

- The upper part, or filum terminale internum, measures some 15 cm in length and reaches the level of the lower edge of the second sacral vertebra. It is located within the thecal sac and surrounded by the nerves that make up the cauda equina.

- The lower part, or filum terminale externum, lies in close contact with and is coated by the dura mater; it extends from the vertex of the thecal sac at S2 to the posterior part of the first-second coccyx segment.

References

- Mercedes Arias, Alfonso Iglesias, Beatriz Nieto, Cristina Ruibal, Jorge Mañas, Rosa Martínez Presentación del tema: “Patología del filum terminale “Una mirada atrás” Unidad de Diagnóstico por Imagen (GALARIA) Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo

- Dr. Miguel B. Royo Salvador (1996), Siringomielia, escoliosis y malformación de Arnold-Chiari idiopáticas, etiología común (PDF). REV NEUROL (Barc); 24 (132): 937-959.

- Dr. Miguel B. Royo Salvador (1996), Platibasia, impresión basilar, retroceso odontoideo y kinking del tronco cerebral, etiología común con la siringomielia, escoliosis y malformación de Arnold-Chiari idiopáticas (PDF). REV NEUROL (Barc); 24 (134): 1241-1250

- Dr. Miguel B. Royo Salvador (1997), Nuevo tratamiento quirúrgico para la siringomielia, la escoliosis, la malformación de Arnold-Chiari, el kinking del tronco cerebral, el retroceso odontoideo, la impresión basilar y la platibasia idiopáticas (PDF). REV NEUROL; 25 (140): 523-530

- M. B. Royo-Salvador, J. Solé-Llenas, J. M. Doménech, and R. González-Adrio, (2005) “Results of the section of the filum terminale in 20 patients with syringomyelia, scoliosis and Chiari malformation“.(PDF). Acta Neurochir (Wien) 147: 515–523.

- M. B. Royo-Salvador (2014), “Filum System® Bibliography” (PDF).

- M. B. Royo-Salvador (2014), “Filum System® Guía Breve”.